We are now over 7 months into the Russo-Ukrainian war. Thousands of casualties have been reported on both sides, both civilians and soldiers. The death toll of military casualties has been kept as a guarded secret, by both the Russian and the Ukrainian side. In July 2022 the British military estimated that 25,000 Russians had been killed, with tens of thousands having been wounded. In August 2022, Pentagon officials stated that around 70,000 to 80,000 Russians had been killed or wounded, with a number of deaths leading up to 20,000. These estimated numbers of casualties were based on satellite imagery, communication intercepts, social media, and media reports. According to Russian Minister of Defense Sergei Shoigu, in his address from the 21st of September 2022, he stated that as many as 5,937 Russian soldiers have been killed since the beginning of the so-called ”special military operation” launched by Russia on February 24th. It is estimated according to the statement made 22nd of August 2022, by General Valeriy Zaluzhnyi, the top commander of Ukraine’s armed forces that around 9,000 Ukrainians had been killed so far on the front. This number could not be independently verified.

Partial mobilization

These numbers will surely just rise with the recent partial mobilization announced by Vladimir Putin on September 21st. His address was initially planned for Tuesday evening but got postponed without any explanation. In his address, Putin announced a partial mobilization, stating that it will apply only to those Russian citizens currently in the reserve, especially those who have served in the military before and have specific military professions and relevant experience. He also mentioned that the mobilization will not cover those who have never seen or heard anything about the army and explained that students can keep going to their classes. Furthermore, Putin also signed a decree that very same day that stated that the contracts of soldiers fighting in Ukraine will also be extended until the end of the partial mobilization period.

Since the address about the partial mobilization 2413 people have been detained all over Russia (21st of September – 26th of September), and these numbers keep increasing. A list of detainees and the number of those detained have been published by OVD-info, which is one of the few organizations providing help and monitoring the political persecution in Russia from within the country’s borders. Vladimir Putin’s spokesman has admitted that there have been cases in which the decree has been violated and that these mistakes will be corrected.

Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu stated that 300,000 reservists would be called up. Shoigu also pointed out that Russia all in all has 25 million potential fighters at its disposal. However, attention has been given to the one paragraph in the published version of Putin’s decree on the official Kremlin website, in which the exact number of the required reservists was omitted. This has led to unrest among those who have not yet been drafted. Russia’s defense ministry has revealed that some occupations will be exempted from conscription, such as IT specialists, bankers, and journalists working for state media. However, light has been cast on the doubts regarding the Kremlin’s pledges to limit the draft. These doubts among others include the fact that just two weeks prior to the announcement of the mobilization, Kremlin Spokesperson Dmitry Peskov informed reporters that there had been no discussion of mobilization by Russian leaders. These doubts are further fuelled by emerging reports of Russian men who do not meet the criteria being called up by local recruiting officers. That same week, prior to the announcement of mobilization the Russian Parliament passed a law that codified a punishment of up to 10 years in prison for those trying to evade the draft. While this law was passed, senior Russian officials along with state media insisted that any mentions of a possible mobilization were part of a Western propaganda campaign.

Regional Disproportions

Protests as a result of the mobilization announcement started to erupt in cities and regions previously quiet. Most of the soldiers sent to Ukraine and killed there come from the so-called ethnic republics, such as Dagestan and Buryatia. In these regions, some explanations include demographics, different attitudes towards military service, large numbers of military units located in these places, low wages and a high unemployment rate. Most reports about the acknowledged death of Russian soldiers are coming from these poorer regions, where the average wage is much lower than the Russian median wage. There were also some attacks carried out on military recruitment offices in the Russian far East cities of Tomsk and Ust-Ilimsk and in the southwest Russian town Uryupinsk. These protests and attacks show a new potentially ethnic division erupting in relation to the recently announced partial mobilization.

New Annexations

The mobilization was followed by a Russian annexation of four Ukrainian territories: Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Donetsk and Luhansk. This annexation was unanimously approved by the Russian lower house of Parliament, the State Duma, approved by President Vladimir Putin’s bills on the 3rd of October. The annexations are to be formalized on October 4th in the Upper House, Russia’s Federation Council; these measures are then to be signed by Putin. The aim of this move is to signal to Ukraine and its allies that the seizure made by Moscow is irreversible. The referendums held in these four regions the week before were just there to signal legitimacy for Russia’s actions for its domestic audience. Internationally these annexations are seen as further problematic as the borders of the territories being seized were not even fixed. Ambiguities also exist in the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk, as neither the Russian military nor its proxies fully control either of those two regions.

Russians on the run

Since Vladimir Putin announced the partial mobilization, as many as estimated 200,000 Russians have fled their country for fear of conscription. The exact number of how many have fled due to the mobilization is hard to determine. Russia shares borders with 14 different states, stretching from China and North Korea to the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The opinions are different on how huge of an impact this exodus will have on the mobilization of the Russian army, as many millions of people will not have the means or opportunities to leave Russia in order to escape their drafting notices. Even though thousands of Russians have managed to leave in order to avoid mobilization with many more probably being forced to be stuck in Russia, it is important to also remember and mention the previous Russian exodus which followed as a direct effect of the war in Ukraine. Just in the first three months of the year 2022 almost four million people left Russia, this included people who worked as IT specialists, journalists, researchers and analysts.

Russian demographics

If we look closer we can see that during this year, 2022, Russia has a population of roughly 145,805,944. This high number might appear relatively huge and make the number of potential 25 million potential fighters look relatively small in comparison. But to understand the complex nature of Russian demographics one has to look deeper at how many people there are in each age group. Roughly 11.3 million people, between the ages 30-34 were born around or just before the collapse of the Soviet Union. In comparison, around 6.5 million people ages 20-24 were born after the collapse of the Soviet Union, during the chaotic times of the 1990s in Russia.

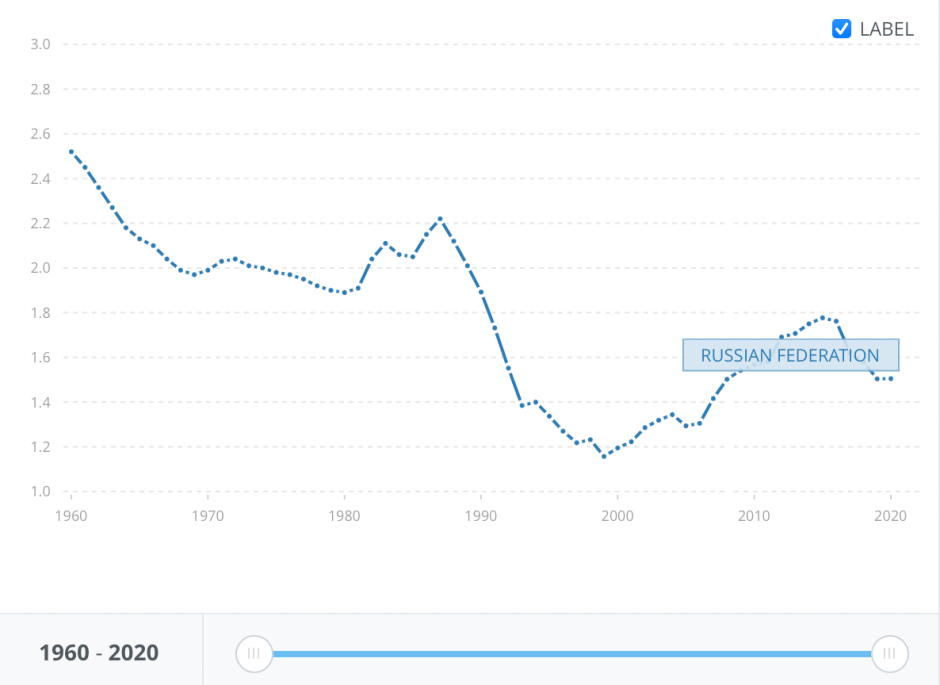

The demographic decline and the unrest can be traced back to the chaos which had its roots in Russia’s post-Soviet transition from a centrally planned economy to a capitalist, market-based one. Some main traits of this decade were economic turmoil, mass unemployment and alcoholism. All of the above-mentioned issues briefly gave Russia one of the world’s lowest male life expectancies. The fertility rate total (of births per woman) dropped significantly and drastically from 1993 to 1999, from 1.4 to 1.2 points. During 1999 Russia’s fertility rate was the lowest it had been for decades. Even though this trend has been changing over the course of the early 2000s, we’re starting to see another decrease in the fertility rate from 2016-2020. In 2016 this number was at 1.8, it began to decrease to 1.5 in 2020 according to statistical data provided by the World Bank.

The ”Brain drain”

The war in Ukraine which was started by Russia, as well as the recent mobilization, have not been the only factors that have led Russians to leave their country. In a report from 2019 compiled by the Atlantic Council think tank, human capital has been fleeing Russia for years. Since Vladimir Putin came to power and became president, a number of between 1.6 and 2 million Russians have left their country for Western democracies. The exodus increased further when Putin returned as president in 2012 along with a weakening economy and growing repressions from the state against its citizens. In this report, the previous wave of emigres from Russia included people with higher education in the social sciences fields, 41% (in fields such as economics, political science, sociology etc.). With recent events, such as the mobilization these proportions might now change. As this event is still relatively new to the world it is hard to measure its impact on Russia at large. But what can be said is that the Russian brain drain will likely continue to take place, making it harder and harder for the Russian society to keep all of its functions running smoothly. Especially now when younger men are leaving the country on a much greater scale than before. This will likely affect not only the brain drain but also the possible number of new recruits of younger age and the demographic decline in a country with an already exceptionally low fertility rate.

How is this mobilization likely to affect Russia?

The mobilization has shown many cracks in the Russian regime, and most of all showed the world the widespread fear of Russians becoming conscripts in this war. In order to make his army successful Putin will have to coerce hundreds of thousands of young men into uniform. This will add to the already existing morale problems that the Russian military is already facing in Ukraine: slipshod organization, poor performance, heavy losses and exhaustion. In addition he will also have to mobilize public opinion. The previous bargain between Putin and the people is no longer in place. Russians will no longer be allowed to keep their distance from the state, granting it impunity and receiving privacy in return. The coercion needed to keep the Russians in check will increase even further while growing numbers will try to flee, bribe their way out of the military services or simply desert the military altogether.

Putin’s mindset is closely related to demographics, he sees Russia’s destiny as a matter of how populous the country will be. So through this lens capturing Ukraine is not only about gaining territory that in Putin’s opinion belongs to Russia, it is also about integrating the Ukrainian population of 44 million people. Qualified workers leaving Russia might have a marginal effect on the demographics in the country. However, this type of human capital flight could have an impact on the economy, in the context of already implemented sanctions against Russia.

Historically some mobilizations have prompted revolutionary disturbances in the country. Such as the mobilizations of 1904 and 1914, even back then the ruling autocracy had little difficulty exerting power and political control over its subjects. These mobilizations continued forward with an ultimately doomed war effort. For instance, it took 13 years from the 1904 mobilization to give effect and three years from the 1914 mobilization to get the tsar deposed. Even without popular legitimacy autocracies have many tools to maintain social control, these include suppressing opposition groups, state propaganda and other forms of repression. Many more tools than any democratic government has at hand.

What’s next?

Predicting the future is nearly impossible in this case. But seeing as demographics play a large role in Putin’s war strategy he will not give this one up easily and will likely push Russian people harder to join his army. Seen as the mobilization prompted another exodus from Russia this will most likely lead to an increase in human capital flight as young professionals will seek their luck elsewhere outside of their country. This in combination with the demographic shift and a much smaller generation of young people will create a problem for the economy, as young people will be expected to work harder in order to keep the economy afloat while providing for the older generations. The human capital flight will pose a problem depending on how many highly skilled professionals will leave and which sectors will have to be filled with new work power.

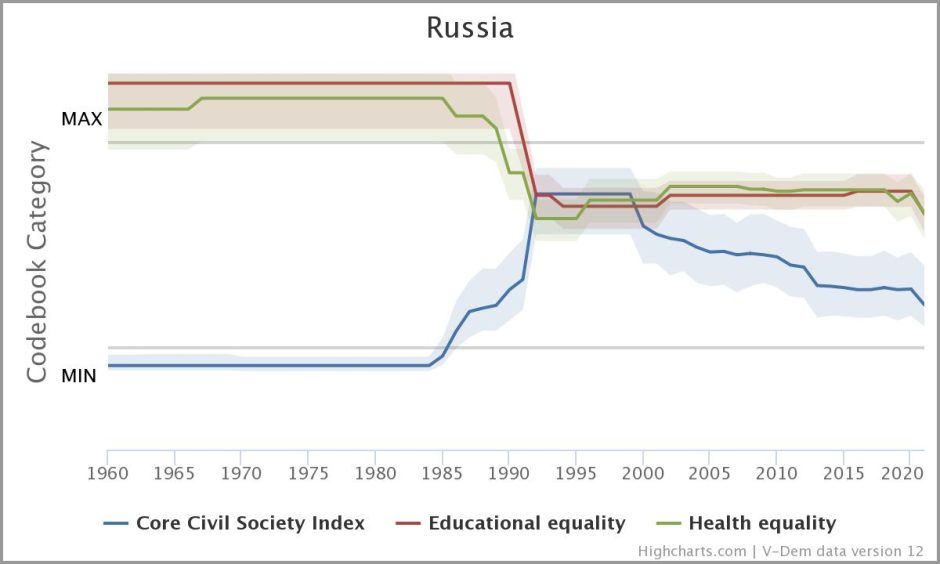

Currently, the Kremlin claims that people in three sectors (IT, banking and state media) will not be covered by the announced mobilization. But protests all around Russia tell us a different story of people not widely convinced by Vladimir Putin’s mobilization, that dying for the motherland is far from every Russian person’s dream. On top of that a society working properly will need more professions in order to keep the birth rate and living standards sustainable, a functioning educational system and proper health care are also crucial for long-term economic growth and prosperity. These changes will likely affect common people and not the ruling elite, at least from a historical perspective of autocratic regimes in Russia. As seen now the rights of civil society have been decreasing dramatically over the last 20 years. Educational equality and health equality have not changed drastically over the last 20 years but they are still not on the same high level as they were back during Soviet times. Just from 2020 to 2021, over the course of one year, all three indicators for the core civil society index, educational equality and health equality started to experience a decrease in scores for a more negative turn.

The continuation of an era or a new beginning? Last but not least, a few important factors will most likely decide the future of Russia. One of these is whether Putin’s goals in Ukraine will be achieved in order to sway the public opinion into thinking that Russia will win this war. Another crucial long-term issue will be the effects of the brain drain on the Russian economy (as a result of the mobilization and Putin’s autocratic politics over the last decade). And last but not least the demographic shifts and a generational gap as a legacy from the 1990s, making the Russian war machine dwindle in size if it turns out that this war will last for years to come. On top of that, some ethnic tensions are on the horizon, tensions previously not heard of on this scale. One thing is sure, Putin’s war is slowly involving a larger portion of Russian citizens, personally affecting their lives. The question remains to what extent current issues will be addressed by the current leadership in Moscow, and what will be the price its citizens will have to pay if the wheel of repression keeps on turning.

Magdalena Kamont

Master student of the "International Administration and Global Governance" programme at the University of Gothenburg. Currently writing her master thesis on democratic decline in Poland. Former intern at Sida.