The Hungarian Stance on the Russian-Ukrainian War

Over the course of recent months, there has been a rift between Hungary and the rest of the European Union member states on the issue of military aid to Ukraine. On December 12th 2022 the EU decided to lower the amount of a proposed funding freeze in exchange for the government in Hungary lifting its veto on an aid package to Ukraine. In fear of losing €7.5 billion in EU funds, Victor Orbán has been blocking an €18 billion EU aid package for Ukraine and a minimum global corporate tax rate. The EU then agreed to lower the suspension to €6.3 billion, while also approving Hungary’s spending plan for its recovery funds. These funds amount to €5.8 billion and will be released after Budapest completes 27 anti-corruption and judicial independence reforms. This money was suspended due to concerns regarding democratic backsliding in Hungary. Hungary’s reluctance for military aid for Ukraine, the relationship between the two countries, and the role which Russia plays are all connected into a larger whole.

Polarization of Hungarian society, through a division of Us versus Them, escalated before 2010 and increased significantly thereafter, when Prime Minister Viktor Orbán came to power. The ruling party Fidesz consolidated its hold on power and opted for anti-pluralism through the erosion of checks and balances, press freedom, and the change of electoral rules to their advantage. Over the course of the year 2022, the ruling party Fidesz won another two-thirds majority in the national elections held in April 2022. Human Rights Watch reported that independent journalists, media outlets, and civil society organizations continued to experience vilification by high-ranking public officials and pro-government media. At the same time, the discrimination towards the LGBTQI+ community continued, along with discrimination towards women and the Roma population. The pushback of migrants and asylum seekers to Serbia was also present and access to asylum procedures was close to impossible. Furthermore, Hungary is also still under the scrutiny of the European Union institutions under Article 7, the EU treaty mechanism which holds governments accountable in the breach of the rule of law.

Friend or Foe

Even though Hungary is part of NATO, it has not allowed weapons to be transported through its territory. The landlocked country is dependent on cheap Russian oil and gas, something which has allowed Orbán to keep the energy prices in Hungary low and allowed him to win broader popular support. The public opinion in Hungary also shows that the general public seems to share some of Orbán’s perceived Russian-friendly attitude. When comparing Poland and Hungary, two countries with opposite opinions on the war in Ukraine, a YouGov poll from October 2022 showed that 65 percent of Poles support maintaining sanctions against Russia, the number for Hungary in turn was 32 percent. At the same time, while three-quarters of Polish citizens blame Russia for the war, this number is much lower in Hungary (only 35 percent). This duality is also seen politically, for instance during the recent voting in the United Nations General Assembly. 141 countries voted and 7 against the resolution put forward by Germany calling for peace in Ukraine as fast as possible. Hungary was one of the countries that voted in favor of the resolution.

Views on help for Ukraine vary even among seeming allies within the European Union. Poland and Hungary share a common view on the rule of law and the role of the EU institutions. However, while Poland remained a strong supporter of Ukraine in the war against Russia, Orbán has described Ukraine’s president Zelensky as his ”opponent” and blamed the EU’s policy towards Russia for inflation and rising energy prices. Since the war broke out on February 24th 2022, Polish-Hungarian relations have not remained as strong. At the same time, Orbán himself has expressed that an independent and sovereign Ukraine is in Hungary’s national interest. He stressed that Hungary is not interested in decoupling the European and Russian economies once and for all and that is why they try to save all that they can from Russian-Hungarian economic cooperation. In his State of the Nation address on February 19th 2023, Orbán also highlighted his opinion on the war in Ukraine and the response of most of the European countries which are currently helping Ukraine.

The duality in Hungarian-Ukrainian relations are also seen in the amount of aid that Ukraine has received from Hungary since the war started on February 24th 2022 up until January 15 2023. According to data provided by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy Hungary ranks in place 33, with 0.05€ billion pledged in humanitarian aid. The amount of aid given is 0.03 percent of Hungary’s GDP in total and 0.27 percent of the GDP of EU aid to Ukraine.

Hungarian-Ukrainian Relations

Relations between the two countries have varied over the course of time. The relations got worse with restrictive language policies in Ukraine, which affected both the Hungarian and the Russian minorities in Ukraine. The law requires the use of the Ukrainian language in most aspects of public life, it also requires all Ukrainian citizens to know the state language. A criticism of this law also came from the Russian regime, claiming that it could lead to further divisions within Ukrainian society and impose limitations on the use of the Russian language in the country.

Even though economic and political cooperation has been functioning without huge obstacles since the 1990s there has been a certain level of concern on the Hungarian side regarding the rights of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine (some 150 000 people according to the census conducted in 2001). This particular minority forms a dense group in certain areas of the Zakarpattia Oblast; it accounted for 12 percent of its population in 2017. Hungarian schools, even though Hungarian schools in Ukraine have been provided with an autonomous education system, with Hungary as the language of instruction, these schools have been chronically underfunded. They, therefore, have received financial and material support from Budapest. The underfunding along with the proximity of the Hungarian border has led the minority to poor integration with the Ukrainian community.

At the same time, Orbán has kept close ties to Russia with similarities in their respective concepts of the state, such as authoritarian posturing and illiberalism between Putin and Orbán. In June 2022, the Hungarian regime asked to exempt the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Kirill, from EU sanctions. Furthermore, the Hungarians now have one of the largest Russian embassies in Europe, since it declined to expel Russian diplomats from their country. Some fears include the use of Budapest as a base for spying operations. One such situation already took place in November 2022, when the Ukrainian security services detained a former officer at the Hungarian border. The detainee was said to have carried information about the Ukrainian military and intelligence personnel on a flash drive.

Playing Both Sides

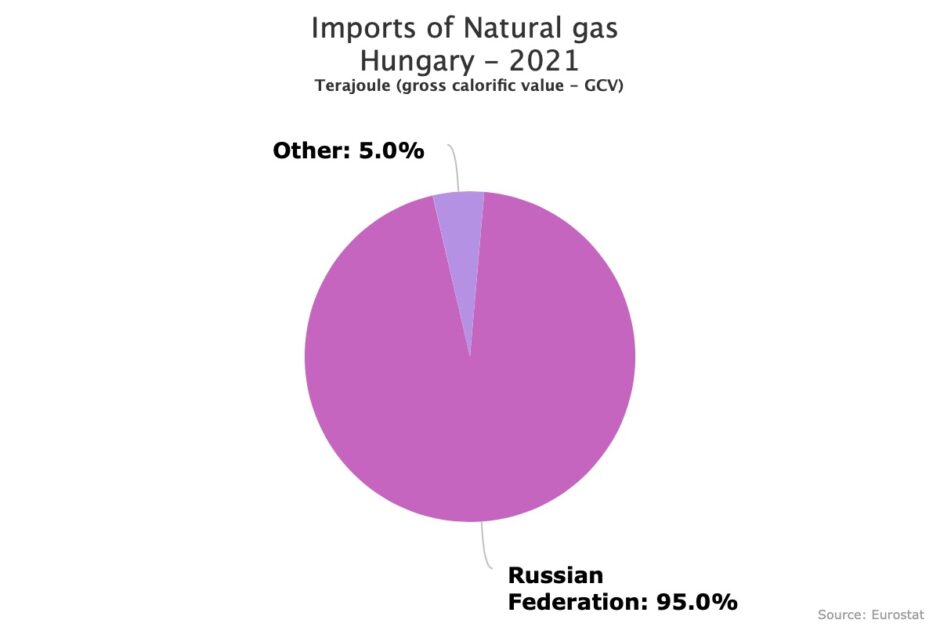

Orbán’s split rhetoric on the War in Ukraine shows his effort of trying to gain political gain wherever and whenever he can. For years he has been implementing a dual foreign policy. He has been trying to enjoy the benefits of the EU and NATO while still maintaining close ties to authoritarian regimes in Russia and China. One such example is the construction of two new nuclear reactors by the Russian state-owned Rosatom. The permit was issued already in August 2022 as part of a 2014 deal between Russia and Hungary, aiming to expand Hungary’s only operating power station. According to data from Eurostat, in 2021 more than half of Hungary’s energy sector consisted of gas and oil. Nuclear energy amounted to only 14,8 percent in 2021. Most of the natural gas (95 percent) was imported from Russia, while 40,9 percent of oil and petroleum products were imported from Russia.

Total Energy Supply

Imports of Natural Gas

Imports of Oil and petroleum products

Orbán’s positive attitude towards Russia might be seen as a way to prove loyalty to Moscow, to court favorable investments from Russian business in Hungary. It can also be seen as a way to gain favor from Russian President Vladimir Putin, in case Russia wins the war in Ukraine. That is why Hungarian efforts to remove several Russian businesspeople from the EU sanction list did not come as a surprise. Moreover, the ties between Orbán and Putin can also be seen in other areas of politics. Hungary in 2021 passed a law banning access by those under 18 to material that promotes or portrays ”divergence from self-identity corresponding to sex at birth… or homosexuality”. A similar ”Gay ban” law was adopted in Russia already back in 2013. Other similarities include the bashing of Western liberal democracies for their lack of ”traditional values”, centralization of the media, and attempts to liquidate and eradicate any independent or critical media by attacking the freedom of speech. Last but not least is the condemnation of foreign-funded organizations.

Future Prospects and Outcomes

As much as Hungary is highlighting its need for peace and avoidance of war, it seems like the Hungarian regime is still trying to make the most of a difficult situation. In trying to balance the need for peace with economic gain, the country’s leadership is using its veto right to negotiate aid for Ukraine with the money previously held hostage due to allegations of democratic backsliding. The crucial issue will become how far the EU will be willing to let go of its principles in the Hungarian case, in favor of aid for Ukraine. Meanwhile, Orbán seems to be getting the best of both worlds. He maintains good relations with Russia due to the expansion of the nuclear energy sector while opting for exclusively humanitarian aid for Ukraine. At the same time, he has created a significant distance between his own country and former allies in the EU, such as Poland, but also the countries within the EU who regard the human rights situation in Hungary as problematic. Most probably Orbán is seeking to ally himself with Putin now to make Hungary independent energetically and economically. With a majority of its energy coming from nuclear power plants, Hungary would no longer have to rely on another country for its energy supply.

This move is distancing Orbán from the EU both on an ideological and economic level. If not for the EU holding him back Orbán would not have to worry about conforming to any standards of human rights or democracy, and the way to a Russian-like autocracy would be wide open to him. What is and probably will continue to be a problematic issue is how far the EU will be willing to go in order to accommodate Hungary, give aid freely to Ukraine and prevent the democratic backsliding from affecting common policy. Will rule of law, democracy and human rights weigh more than any form or aid for Ukraine or will there be a third way out of this uncertain scenario? As for now, only time will tell.

Magdalena Kamont

Master student of the "International Administration and Global Governance" programme at the University of Gothenburg. Currently writing her master thesis on democratic decline in Poland. Former intern at Sida.